One Hundred Years of the Cairo Museum

Zahi Hawass

The Cairo Museum is a portal through which the visitor is transported back to the mysterious realm of Ancient Egypt. It holds the treasures of the greatest civilization in the world.

This year is the centennial of the creation of the first permanent Egyptian Museum.

On December 9th, 2002 at a centennial celebration over two hundred and fifty hidden treasures of Ancient Egypt will be unveiled. I would like to recount how this new exhibit came about.

The Cairo Museum is a portal through which the visitor is transported back to the mysterious realm of Ancient Egypt. It holds the treasures of the greatest civilization in the world.

This year is the centennial of the creation of the first permanent Egyptian Museum.

On December 9th, 2002 at a centennial celebration over two hundred and fifty hidden treasures of Ancient Egypt will be unveiled. I would like to recount how this new exhibit came about.

As the centennial of the Cairo museum approached I began to dream of an international celebration. I spoke

with Farouk Hosni, the Minister of Culture, and he encouraged the idea and added that the museum should have a face lift for the occasion. The late Hamdi Shehata, head of Museum Sectors, and Mamduuh El Damati,

the Director of the Cairo Museum, and I began to plan renovations for the one hundred year old museum. First: a

new paint job. Second: air-conditioning.Third: exterior lighting. We put this plan into

action, and then we had another idea.

In the basement of the museum, unseen by anyone, was a treasure trove of ancient artifacts. We thought that we should dig into them, and chose the best

100 artifacts for a new display at the celebration. We thought that the mysterious basement rooms would also be a good place for the new exhibit.

When I looked at the artifacts from the basement I was a bit disappointed; they were not as magnificent as we had anticipated. I thought about the artifacts already on display at the museum; the

statue of Khafre, the builder of the second pyramid, and the fabulous collection from the intact tomb of khufu’s mother Queen Hetep-Heres. From the middle kingdom pyramid area were golden treasures.

From the Valley of the Kings the treasures of the golden King Tutankhamen, there was the gold of Tanis. In

fact, it seems the previous curators had already selected the best artifacts,

and they were already on display in the halls of the museum. So we searched for another source for a new exhibit.

Suddenly I remembered that there were many artifacts, all over Egypt, that hadn’t been seen by anyone but the excavators who found them. The committee got together and thought about the beautiful statues that

were discovered in a rock-cut tomb near the second pyramid, by Abou-Bakr in 1962 at Giza, and were neither published nor exhibited. In fact, they were still

stored in the tomb! Between the best objects in the museum basement, and the artifacts stored all over Egypt,

the number of objects soon grew to two hundred and fifty. If we could somehow bring these treasures to the museum, we would be able

to create an unparalleled exhibit to celebrate the museum’s one hundredth

anniversary.

I asked Dr. Mohammed Abdou El Maksoud, the head of the Pharonic section at the Delta, and the director of the Cairo Museum for full authority to open

all the store rooms in Saqqara, the Delta, and Upper Egypt, and to bring the artifacts that were languishing inside the magazines. I obtained the cooperation of the foreign excavators to exhibit their

stored artifacts for all the people to enjoy. I felt that this would help to bridge the gap between the first great

scholars who contributed to the museum; Marriette, Maspero, and Ahmed Basha

Kamal, to current excavators both foreign and domestic.

Another committee was appointed to decide on the location of the exhibit. Among them were Egyptologists and my friend the artist, Mahmoud

Mabrouk. The Egyptologists felt that the exhibit should be inside the hall at the

Museum, but Mabrouk thought it should be in the basement. There was a lot of objection to this idea, but I was intrigued by the

idea of a unique and unknown location, and the possibility of unveiling “The Hidden Treasures of Egypt” in an exotic setting. I called on Dr. Hussien El-Shabory, the architect who designed the Museum

at the Library of Alexandria, to see if he could design an exhibit that would be appropriate and overcome the objections. Dr. El-Shabory saw that an area running east and west, and located at the far north

of the basement, could be quickly renovated and would be large enough to house the exhibit. So, after much deliberation by the committee, this location was selected. The only problem now was time, and the task ahead seemed overwhelming.

The location of the artifacts reached far and wide including areas in the Delta; Taba, Quesna, Tanta, Tell-Basta, Gizireh Mutaua, Hassan Dawaod, Minshet Ezat, Tell-El Daba,

Mersi-Matrouh, and from the underwater excavations in Alexandria. In Upper Egypt the sites included Giza, Saqqara, Luxor, and

Sohag. We put together a committee for the collection of the sought after artifacts. They traveled to the sites to transport the objects from the

magazines. It was like Mission Impossible!The objects soon began to arrive in Cairo by car, truck and airplane, and

all within fifteen days. I was constantly on my cell phone helping with logistical problems, and reassuring

worried committee members, not to mention; the movers, the inspectors, and the foreign archaeologists. However, arriving both day and night, the artifacts came

to the museum safely.The cooperation between all those involved was unprecedented.

Adventures in Transporting the Artifacts

.jpg) One of the most exciting adventures was to bring the sarcophagus of Horwdja, dated to Dynasty 26, from Quesna, about 57 km. north of Cairo. It had been discovered in October 1992.

Horwdja, with his father and brothers held the title of priests of the Djed-pillar at the house of the God. One of the most important scenes found on the sarcophagus was the scene

of the family of the priest Hor-Djed. They are standing in front of the sacred tree with Isis and her sister Nepthys.

Another beautiful scene is that of Anubis sitting on a mummification tent. On the sarcophagus are twenty seven lines of hieroglyphics from the book

of the dead, representing about eighty nine chapters. Made of black granite, and weighing approximately 20 tons, it is 241 cm.

long, 100 cm. wide, and 145.5 cm high; moving it was going to be an enormous task.

One of the most exciting adventures was to bring the sarcophagus of Horwdja, dated to Dynasty 26, from Quesna, about 57 km. north of Cairo. It had been discovered in October 1992.

Horwdja, with his father and brothers held the title of priests of the Djed-pillar at the house of the God. One of the most important scenes found on the sarcophagus was the scene

of the family of the priest Hor-Djed. They are standing in front of the sacred tree with Isis and her sister Nepthys.

Another beautiful scene is that of Anubis sitting on a mummification tent. On the sarcophagus are twenty seven lines of hieroglyphics from the book

of the dead, representing about eighty nine chapters. Made of black granite, and weighing approximately 20 tons, it is 241 cm.

long, 100 cm. wide, and 145.5 cm high; moving it was going to be an enormous task.

The committee went to Quesna to see the sarcophagus. Tarek El Awady, my assistant, took Ken Garrett, the national

geographic photographer, to make a photographic record of the adventure. Abdou El Hamied Kotb, Chief Engineer at the Giza pyramids, brought his

team: Talal and Ahmed El Kiriti, who are trained to move heavy objects. The El-Kiriti brothers have worked with me in moving heavy stones and

sarcophagi on the Giza plateau. On first sight the committee thought the sarcophagus would be impossible to move it because it was located on a seventeen

meter high mound, and sitting between mud-brick archaeological features. Located in the far end of the archaeological site, it was impossible to

use any heavy equipment because the weight of that equipment would destroy the site. Everyone soon realized that the only way to move the sarcophagus was over

a section of agricultural land adjacent to the site. Fortunately the owner of the land agreed to let the workmen cross over his land with the equipment.Using the same method of the ancient Egyptian workmen, Abdou El Hamied’s team tied the sarcophagus with ropes and pulled it onto wooden sledges. Using iron bars they dragged it while the workmen chanted, “Sali Elieh….Sali Elieh” (pray on him), to help with the rhythmic movement.First the lid, and then the sarcophagus were loaded onto a truck for the

ride to Cairo. The sarcophagus arrived at the museum, and the same method was employed to move it to its exhibit location. On its arrival we discovered that it was too large to move into the

exhibit space. It will be exhibited outside on the west side of the basement.

Another heavy statue came from the Delta, and it will be exhibited next to the

sarcophagus. It is the black

granite statue of the Horus in the Hawk form, dated to the late period. The statue represents Horus standing on a rectangular base designed for

hieroglyphic inscription, although the artist chose to leave it blank. Superb detail, especially on the body of Horus, makes it one of the best

sculptures of this period. The height of the statue is about 122 cm. and the width is 52 cm. The statues were inside the Tanta Museum, but were never on exhibit for

the public. The same method described above was used to move it to the Cairo Museum.

The incoming artifacts were stored in another area of the vast basement, and it became an interesting place for people to

visit. Nadia Lokma and her team, took on the restoration and

conservation of the artifacts, and Ken Garrett spent many days photographing

them. We decided to publish a catalogue of the one hundred most interesting artifacts representing one hundred

years of the Cairo Museum. Another book about the exhibit will be published in co-operation with the AUC press and

the National Geographic.

Stories of the excavation

Archaic period: The excavations of early Dynastic tombs in the Delta.

The most important artifact in the exhibit, from the Archaic Period, is the Palette of the Solar Animals. It was discovered on private land owned by a famous Egyptian Composer, Kamal El Tawiel,

who is a good friend of mine. According to Egyptian law, artifacts or monuments on any land located near archaeological sites, or any land with evidence of

antiquities, or the possibility of discovery of antiquities is controlled the government. If an individual purchases land, and is aware of artifacts, or

possible artifacts then they become responsible for the cost of excavation. The law states that the Director of the Supreme Council of Antiquities

should appoint a committee to decide who will pay for the excavation. So even though this land was owned by my friend, the decision was that

this land owner must pay for the excavation.

In September, 1998, in a village called Minthet Abuu Ezat, located near the town of Sinbalwien in the Delta, the excavation, under archaeologist Salem

Gabra El Bagdady, began. A large cemetery was unearthed, with certain tombs dating to Dynasty 1, and a great surprise was that the tombs were rich with funerary objects. It is most likely the richest archaic cemetery recently discovered in

Egypt. A beautiful palette, broken into 5 pieces, was discovered and when restored found to be missing its top. The scenes on this palette are unique. It depicts animals, such as a hunting dog followed by an animal with long

legs resembling a Gazelle, and behind the dogs is another Gazelle. In the middle of the palette are two animals facing each other with long

raised tails, and long necks curved around each other which represents the unification of the two lands. The circle formed by the intertwined necks was used to mix Kohl, eye makeup used in

ancient Egypt, so this palette probably sat on the dressing table of a wealthy Egyptian.

Old Kingdom: Excavation of the Pyramid Builders in Giza.

In 1990 excavations began at what was to become the cemetery of the pyramid

builders. The accidental fall of a horses hoof through a hole, uncovered the first tomb. The cemetery is located on a hill south of the pyramids of Giza.

The first tomb was a family tomb prepared with three false doors, the first for a man named Ptah-Shepsesu, and the others for his wife and son. The tomb also contains a small open courtyard.

The walls incorporate what appear to be left over stones that were used in the construction of the pyramid, temples, and official tombs. Nearly six

hundred small tombs of a variety of styles, and seventy more elaborate tombs were found at this site. Up to 6

ft. high many tombs have pyramidal shapes, some like beehives, and some like gabled roofs. Others have miniature

ramps and causeways, and some are miniature mastabas. In shafts under the tombs, simple rectangular burials contain skeletons

of the owners, whose budgets did not include mummification.

In 1990 excavations began at what was to become the cemetery of the pyramid

builders. The accidental fall of a horses hoof through a hole, uncovered the first tomb. The cemetery is located on a hill south of the pyramids of Giza.

The first tomb was a family tomb prepared with three false doors, the first for a man named Ptah-Shepsesu, and the others for his wife and son. The tomb also contains a small open courtyard.

The walls incorporate what appear to be left over stones that were used in the construction of the pyramid, temples, and official tombs. Nearly six

hundred small tombs of a variety of styles, and seventy more elaborate tombs were found at this site. Up to 6

ft. high many tombs have pyramidal shapes, some like beehives, and some like gabled roofs. Others have miniature

ramps and causeways, and some are miniature mastabas. In shafts under the tombs, simple rectangular burials contain skeletons

of the owners, whose budgets did not include mummification.

Many women are named in inscriptions. It appears that the wives and daughters of the workers held positions as

priestesses of Hathor or other goddesses. The statues and hieroglyphs indicate a family centered lifestyle, wherein the

construction of ceremonial centers and pyramids were looked upon as a labor of love and a national project. One statue of a beautiful seated woman named Hepeny-Kawes depicts her with large

eyes and a well modeled body, under a long white robe. This is typical of old kingdom artistic representation. Found with Hepeny-Kawes was the figure of a

woman grinding grain. She bends over her grinding stone, supporting her full weight on well muscled arms, while she rolls a heavy pestle over the grain. Women were generally buried with their husbands. Those women in higher

positions, such as a high priestess and two female dwarves, have their own tombs. Other statues depict butchers, brewers, potters, and bakers. The statue of the baker is particularly interesting.

It shows a man kneeling in front of his oven, his head is turned to the left, and he holds his hands in front of his face to shield it from the fire.

During this excavation we discovered a ramp leading up hill to another cemetery. The upper level of

burials is much more elaborate and contained artifacts, inscriptions, and were constructed of stones of higher quality. Many

of the skeletal remains were found in wooden coffins, although still not

mummified. The tomb architecture is

mastaba-like, and much larger than in the lower cemetery. Some were made of limestone with mud-brick cores, or were rock cut.

The inscriptions are of overseers of the draftsmen, masonery workers, craftsmen, and one title was “the Director for the King’s Work.

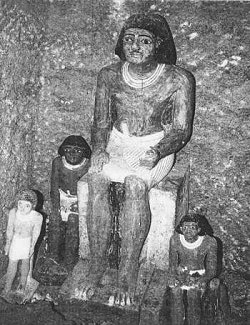

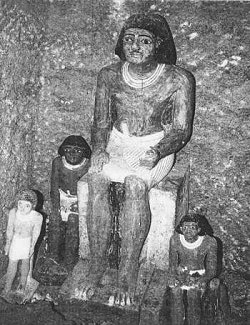

From this upper cemetery, and part of this exhibition, are the statues of Inty-Sdu found in the Serdab of his tomb. Cut into

bedrock, and intact, Inty-Sdu’s tomb had a simple niche in the wall covered with mudbrick. We noticed this

because there was a small hole in the wall. I peered inside the niche with a flash light and staring at me were the eyes of a statue.A far greater surprise awaited me after I removed the mudbrick covering

the niche.Four statues stared back at me. The middle statue is the largest and is flanked on the right with two

smaller statues, and on the left is another small statue. We discovered the remains of a fifth wooden statue which had stood at the

far left.Disastrously, when we opened the tomb, the flow of oxygen had instantly disintegrated it. This wooden statue must have been added after the others were finished in

order to fulfill the ancient Egyptian appreciation of symmetry.

From this upper cemetery, and part of this exhibition, are the statues of Inty-Sdu found in the Serdab of his tomb. Cut into

bedrock, and intact, Inty-Sdu’s tomb had a simple niche in the wall covered with mudbrick. We noticed this

because there was a small hole in the wall. I peered inside the niche with a flash light and staring at me were the eyes of a statue.A far greater surprise awaited me after I removed the mudbrick covering

the niche.Four statues stared back at me. The middle statue is the largest and is flanked on the right with two

smaller statues, and on the left is another small statue. We discovered the remains of a fifth wooden statue which had stood at the

far left.Disastrously, when we opened the tomb, the flow of oxygen had instantly disintegrated it. This wooden statue must have been added after the others were finished in

order to fulfill the ancient Egyptian appreciation of symmetry.

The four statues are inscribed,

“The overseer of the boat of the goddess Neith, the King’s acquaintance, Inty-shedu”

The faces of the statues were particularly interesting. After some debate we decided that the artist had depicted the boat

builder at four stages of his life. The large statue in the middle is a portrait of Inty-Shedu just before his death.

The two flanking statues characterize his youth, and the last on the right show him at an older

age. The muscular features on each statue are representative of the age it depicts.

These five statues relate to the five statues of the pharaohs, which were part of the pyramid temples from Khafre to the end of the

Old Kingdom. It was a thrilling discovery, and it was decided that Farouk Hosni, Minister of Culture, should

announce the discovery but the 1993 earthquake interrupted the event, and the discovery remained unannounced until now.

Other interesting tombs include that of Nefer-Theith and his primary wife Nefer-Hetepes, his secondary wife, who has an inscription saying “midwife”,

and eighteen children. The stela and three false doors are inscribed with beautiful hieroglyphics, and unique scenes of grain grinding, and bread and beer

making. Other scenes include fourteen types of bread, cakes, onions, beef, grain,

figs, and a man making beer, and also another pouring the beer into jars.

The tomb of the man named Petety is unique in its form. It has three open courts. The husband and his wife Nesy-Sokar are depicted separately, probably because she

was a priestess of the goddess Hathor and Neith. Her tight dress leaves bare breasts, and she wears a collar

and a broad necklace. Her hair is divided in front and behind her shoulders. Her head is tilted slightly up and forward, perhaps because of the wide,

tight collar. The bold, confident expression is enhanced by the following curse,

“Listen all of you! The priest of Hathor will beat twice any of you who enters this tomb or does harm to it.The gods will confront him because I am honored by his Lord.The gods will not allow anything to happen to me.

Anyone who does anything bad to my tomb will be eaten by the crocodile, the hippopotamus and the lion.”

This cemetery has been dated from 2551 to 2323 B.C. from Dynasty 4 to the end of Dynasty 5. Eighty percent of the cemetery may still be under the sand along the hill. We believe today that many of the workers of the tombs were conscripted

farmers, who would come to work during the time of the Nile inundation when working the farm was impossible. These workers are depicted in many paintings and

reliefs. They are never depicted as slaves, but their style of dress

and manner is that of peasants. The full time workers are represented in the cemeteries, but part time laborers were most likely buried in their various villages throughout Egypt, as they would have returned to be buried with their families upon illness or accidental death.

Below the cemeteries, Mark Lehner is currently excavating a large section below the cemeteries, which from all appearances is the workman’s village. In Deir el-Medineh, 1500-1163 B.C., a new Kingdom cemetery quite similar to this one has been

excavated. Dr. Lehner found areas for baking bread, salting fish, metal working, and craft

shops. The area has paved roads, and bunk-like room for sleep.In this village were the builders and artisans of the tombs in the Valley of the

Kings. It is thought that this type of organized labor of national projects lasted until the end of the pharaoh’s monumental building

efforts. There is no evidence that slaves were ever used in the building of these monuments.

There is; however, evidence that the workers worked hard and suffered injuries.

When comparing skeletons from the upper cemeteries and the workers graves, the upper class were healthier

and lived longer. Degenerative arthritis of the back and knees was more severe in the lower tombs. Simple and multiple fractures were present in both cemeteries, and most

show signs of splinting since they healed completely and with good alignment in both cemeteries. Two cases of amputations healed correctly. Some fractures of the skull were noted, but all were evidently caused by one on one

confrontation. There is also evidence of emergency treatment of injuries by trained physicians, and one skull

shows evidence of brain surgery. There is no evidence of mistreatment in the case of the workers.

Excavating the Tomb of the Dwarf, Per-ni-Ankhu

In the tombs of the Western Cemetery at Giza there is a tomb that had been discovered by the American, George Reisner. It had belonged to a man named

Nswt-Nefret. Near this tomb is the tomb of the now famous dwarf, Seneb which had been discovered by the German, Herman Junker in the last century. I thought that I would clean the piled up sand from around these tombs because I

needed to publish the titles of the owners, and during this cleaning we discovered the tomb of the dwarf Per-ni-Ankhu. I was ecstatic over this because it was my first tomb of a dwarf.

The newly discovered tomb is of a rectangular shape with an attached serdab, which we discovered from an opening in its ceiling. When I took the ceiling out, and looked inside, I saw the face a statue.

The statue of the dwarf is an example of superb craftsmanship. Of basalt, the sculpture is simple and clean. The

dwarf is handsome with a look of serenity, yet he exudes strength and power. He has a young face, yet he appears wise. On the right leg is an inscription,

“He who pleases his majesty everyday”

It is an unusual statue because most statues carved of basalt, with this

advanced technique, are for royal people. This indicates that the royal sculptor carved it for Per-ni-ankhu. The statue depicts

several deformities of the shoulders and legs typical in dwarfism. When compared to the skeleton, found in the burial shaft, the style is

representative of the type of sculptural realism common to this period. The study of the location and tomb inscriptions of Seneb and Per-ni-Ankhn tombs,

indicate that the father of Per-ni-Ankhn was not a dwarf. With the study of the skeletons, we can suggest that Per-ni-Ankhn is

probably the father of Seneb. Therefore, it is regarded as a masterpiece of Old Kingdom sculpture. With the dwarf were two statues of his two wives. The statues are dated to Dynasty 4 based on the style of the tomb, and

the artistic style of the statues.

The serdab containing the statue of the dwarf was inscribed with an illustration of the dwarf standing in the palace, and the phrase,

“One known by the King”, the dwarf in the great palace, Per-ni-ankhn

I went down and I took it with my hand and it was a memory that I will never forget, although this discovery was followed by the excavation of sixty

five fabulous old Kingdom tombs.

The Tomb of Kai

One of my favorite statues in the exhibit is that of the priest Kai, and was found inside his small, beautiful, and unique

tomb. The tomb is so richly decorated that I call it the Nefertari of Giza.

At the entrance of this tomb is a unique inscription that reads,

“It is the tomb makers, the draftsmen and the craftsmen and the sculptors who built my

tomb. I paid them beer and bread and made them to make an oath that they are

satisfied.”

Also at the entrance is a unique scene of Kai with his daughter. Her two arms are placed affectionately around the neck of her

father. This scene is the first of its kind from the Old Kingdom. One of the scenes shows Kai with his wife standing over several exotic looking

boats. The artist painted the background gray to cover his mistakes when drawing the boats and the people in

them. Other scenes show daily life and an offering list with names of wine and beers. The false door depicts Kai’s titles as the priest of

Snefru, Khufu,

Khafre, and Menkaure. Behind the false door is the burial shaft that contained a beautiful seated statue of Kai

with his daughter and son flanking his sides. Inside the chamber the remains of two wooden sarcophagi, and the skeletal

remains of Kai. Also was a skeleton of a pig. We left Kai in situ to show respect for him and his beautiful tomb.

Beside this tomb we found yet another tomb built by Kai. He built it for his daughter. The four walls depict beautiful scenes

painted on plaster over mud brick. One of the scenes shows his two daughters wearing banded dresses, and in

another a playful greyhound. On the floor is a circular limestone receptacle, which must have contained a decorated

pillar. On it is a unique title:

“One known by the king, the scribe, the waab priest and he who stands before the

king’s children: Kai.”

The Excavations of the Pyramid of Queen Khuit, and the Tomb of Teti-ankh.

At Saqqara, we discovered the pyramid of Queen Khuit near the pyramid of Queen Iput I.

It is about seven meters high. Discovered inside the pyramid was the sarcophagus and another room for four canopic jars.

This pyramid contains much new information on the Chronology of Dynasty 6. Near the pyramid we

found a funerary temple that consisted of a ritual room with three niches, a

ritual chapel, two rooms used as storage, and a room with an entrance.

There are wall reliefs on the temple wall that can give us an idea about the purpose of

the wall reliefs in the funerary temples of the Queens of this period. The scenes found show the king in his relationship with his mother,

titles of the queen. and other scenes of the queens activities in the after life. There, she accompanies Hathor

in a boat sailing in the marshes with Lotus flowers. Offering bearers carry bread, beer, fruit, geese, vegetables and meat

that will be presented to her and Hathor. Also depicted are scenes of the Senet game in its first shape, and the song of hfr which when sung enables the queen to defeat devils in the

afterlife.

The discovery of the tomb of Prince Tetiankh-Km near the pyramids of Iput I, and

Khuit lets us make an important conclusion about the beginning of Dynasty Six. Tetiankh-Km was the eldest son of King Teti. He died during the reign of his father at the age of 25.

Userkara became the king after the death of Teti according to the list of Abydos and Turin (he is not mentioned in the tombs of the high

officials in the cemetery of Teti or in the Saqqara list). Userkare had no relationship with Teti but he was one of the princes who

gained power and tried to get rid of Teti. Therefore, we can now agree with what Manethos

wrote: Teti was killed as part of a conspiracy. After the death of Titian-Km, the legal heir to the throne, Queen Iput I was able to see her son succeed Pepi

succeed. Pepi I changed the mastaba of his mother to a pyramid to announce her status as Hathor Isis, which would

help establish his legal right to the throne. This verifies the reason for the disappearance of all the monuments of

UserKara at Saqqara, and also the reason why he ruled for a short period, an estimated 7 years.

In the exhibit are two items discovered in the burial chamber. One is the fabulous alabaster head rest, and the other is a palette of

the seven sacred oils which are in the anniversary exhibit. On the palette is a line of hieroglyphics:

“The eldest son of the King, of his body, the sole friend, the honored one before the great God, Tetiankh.”

The seven sacred oils were used ritually both during mummification and afterward in funerary offerings. The

oils used to help congeal the linen wrappings and in the opening of the mouth ceremony unfortunately helped quicken deterioration of the bodies. The seven

oils are mentioned as early as Dynasty 1, and as late as the first intermediate period. They are listed in several tombs at Saqqara and have been

found outside of Egypt. Not only ceremonial, the oils were used regularly in Egyptian life. Both the stela and the headrest are part of this exhibit.

The plan of the tomb is simple. It has an entrance on the southern side. The

offering chapel has an inscription which translates as:

“The eldest son of the King, of his body, the hereditary prince, the count

The King’s son, the seal bearer of the god, the chief lector priest.

The scribe of the divine words, overseer of Upper Egypt, the sole friend,

The overseer of the two granaries, keeper of Nekheb.”

The chapel walls have inscriptions of scenes of offering bearers, butcher, and animals being slaughtered. There

is a hall with the false door leading to a room which entrance depicts servants in the act of dragging large vessels on wooden sledges. Other walls in this room contain more offering bearers and a badly

deteriorated depiction of the tomb owner with the scepter sign.

The shaft in the burial chamber has a simple entrance on the north wall

of the horizontal hall. It was filled with sand. On the north side of the shaft is the burial chamber, which has 3 holes

possible used by tomb robbers. An unpolished limestone sarcophagus lies directly under the false door in a hall

above. The lid was found raised up on stone, and a hole had been made it its edge and part of the base permitting

perhaps a child to enter. Black soot remains where the thieves used light, and the mummy is in poor condition.

Fortunately he alabaster headrest and stela were escaped the attention of

the thieves.

The Discovery

of the Tomb of the Physician Qar.

A happy accident brought about the discovery of the tomb of Qar, “the Physician of the palace and keeper of the secrets of the king”.

Modern tomb robbers uncovered an adjoining tomb during the night, which

necessitated that I excavate of the area. Found next to the robbed tomb of Ny-Ankh-Nswt, was the tomb of

Qar. It consist of a small complex with a chapel and open court, a

mastaba and burial shaft and chamber, and a wall surrounding the tomb. Although the sarcophagus was opened, some skeletal remains tell us that

the tomb owner was about 50 at death and was free of disease.

Several interesting artifacts were discovered inside. Next to the head of Qar was a collection of copper surgical instruments.

Each has a hole used to hang in a box, and are possibly the oldest surgical tools yet discovered. Other

objects of bronze and wood, including a statue of third dynasty architect, Imhotep were found in a cache outside the tomb.

From Abou Rawash, is a large alabaster bowl chosen for the exhibition. While cleaning around the pyramid located at the site, a Swiss and

Egyptian team discovered the substructure of a satellite pyramid. This small substructure held only two rooms but surprisingly

there was a wonderfully made bowl. Inside the alabaster is inscribed with the Horus name of Khufu in a cartouche. The inscription can be seen only with use of a light against the

transparent material. This bowl had been in the museum basement for a while, and when I brought my friend Dr. Ali

Radwan to examine some of the artifacts we discovered this cartouche. Ken Garrett was able to photograph our looks of surprise and pleasure at

the discovery.

In 1945 Dr. Abdel Nomen Abu-Bakr, professor of Egyptology undertook an excavation of the western field of the pyramid of Khufu. He was forced to store many Old Kingdom statues in magazines and rock cut

tombs around the causeway of the causeway of Khafre. I had been waiting for an opportunity to bring these statues out of

storage since I had seen them a few years ago. I think Abu Bakr would be very proud to know that these statues have

become a major part of the centennial exhibit.

Also part of the exhibit and from About Bakr’s excavation is the statue

of a scribe. When the Minister of Culture, Farouk Hosni, saw this statue his interpretation was that the scribe is

dreaming. Other statues representing workers in the Old Kingdom are, the Baker. In front of the Baker is an oven and his head is turned to the left while he holds his hands in front of

his face to shield it from the fire. From Dynasty 5 is a potter, a double statue of a man and his wife, and

other wonderful statues.

Artifacts from the Middle Kingdom

Representing the Middle Kingdom are statues and scenes with their own

unique style. The high official’s tombs are located in Beni Hassan and El-Bersla. One scene depicts thirty seven Asiatics in their native dress with beards

and coming from the east.

In middle Egypt, at El-Lisht at new capital was established, during Dynasty 12, in order to extend the agricultural land. The Kings, having learnt from the past that pyramids did not protect

their predecessors mummies, decided to build mazes of corridors out of masonry that would confuse would be tomb robbers. These corridors also represented the dark kingdom of Osiris. Traps were set along the corridors and the success of these was proven

when early archaeologists unexpectedly happened upon the corpses of ancient tomb robbers hanging upside down from their legs. The cores of the pyramids above the mazes are built of

mud-brick. Some are covered with limestone from Tura. King Neb-Hepet-Re Mentuhotep, Dynasty 11, built his tomb at Dier el Bahri as a mastaba topped with

a pyramid. From around the mazes made for the Princesses Khnunet, Ita-Set-Hathor, Meret, are caches of jewels

like lapis lazuli, amethyst, and carnelian.

Dynasty 12th is represented by a wooden cosmetic box from Qurnah. Dynasty 13 has two rectangular limestone

stelae. One is named after a lady Senet-It and was discovered in

Abydos. Carved into the face of the second is a big ole honkin' ankh. It is the

ankh sign of Sobek-Hotep. Abydos was the center for the worship of the God Osiris during the middle Kingdom.

The ankh is a symbol of life; water, light, and air, all needed for the after life.

New Kingdom Excavations

.jpg) The New Kingdom, Dynasties 18 to 20 is considered the golden age of Egypt. From the Valley of the Kings

is the tomb of King Tut. Many of the 6000 artifacts have never been seen by the public, and so they will be

included in the hidden treasure exhibit. Recently restored gilded and inscribed leaves that cased furniture, two painted wooden boxes, beautiful and

extravagantly painted wooden boats, a golden pectoral, and a winged scarab holding the sun disk are among the newly restored artifacts. When the conservation team was working on a jewelry box, from the

collection, they were surprised to find a piece of jewelry that had never been catalogued.

The New Kingdom, Dynasties 18 to 20 is considered the golden age of Egypt. From the Valley of the Kings

is the tomb of King Tut. Many of the 6000 artifacts have never been seen by the public, and so they will be

included in the hidden treasure exhibit. Recently restored gilded and inscribed leaves that cased furniture, two painted wooden boxes, beautiful and

extravagantly painted wooden boats, a golden pectoral, and a winged scarab holding the sun disk are among the newly restored artifacts. When the conservation team was working on a jewelry box, from the

collection, they were surprised to find a piece of jewelry that had never been catalogued.

Also in the Valley of the Kings was the amazing discovery of the cachet of Royal mummies. When Brugsch discovered the 40 royal mummies, he removed them

all to the museum you can see some of them, like the famous mummy of Rameses II, in the mummy room of the museum. What was never made public was the fact

that there was a second cachet with 13 mummies, and 3 of them were left in situ before this exhibit. We decided to

bring the mummies to the exhibit. It is believed that they are the son of Amenhotep II, who was 20 years old at

death. A lady of 40 years named Mery-Re-Hatshepsut, who was the main wife of King Thutmosis III, and Queen Ti,

the wife of Amenhotep III and the mother of Akhenaten.

The temple of Luxor, built by Amenhotep III, one of the great Kings of the New Kingdom. From his reign we

will exhibit a quartzite statue of Sebti, the priest of the God Montu. Sebti is in a position of adoration, and holding a small chapel that

contains a miniature statue of Montu in the shape of a Hawk.

From the tomb of Apria at Saqqara, discovered under the antiquities department rest

house by Alain Zivie, is a beautiful and unique sculpture of a fish made of

ivory. The fish is a religious symbol representing the rebirth of the Sun. Also discovered in this tomb is a wonderful head carved of wood

representing the wife of Apria who was the prime minister of Egypt. During the discovery Alan and I entered the tomb, and I was amazed by the

conservation and restoration efforts of the engineers working under Dr. Zivie. He had chosen to hire the men who were building the subway tunnels in

modern Cairo for this excavation, and had gotten good results.

In the exhibit is a limestone sphinx of Rameses II in full Pharonic

regalia. Uniquely this sphinx has hands, instead of paws, and it is holding a jar. The sphinx was found among the many statues in the Karnak cachet

discovered in 1902. The history of this discovery is interesting. In 1899, eleven pillars collapsed in the hypostyle hall of Karnak temple.

Gaston Maspero appointed G. Legrain to restore the pillars in the temple. During construction a hole was discovered in the northwest corner of a

court that had been built by Thutmosis III. Covering the hole were stone blocks with inscriptions that dated to the

middle and new kingdoms. By 1902 Legrain had uncovered over 1000 statues, and astoundingly he continued to

discover statues, some 17,000 bronzes, and wood and stone artifacts until 1905. The dangerous condition of the excavation posed by the water

table caused the remaining artifacts to be left in situ, where they remain today. This find is still the

largest find of statues ever made.

.jpg) A prosthetic big toe discovered still on its mummified foot, is in the exhibit. It was among artifacts recovered from Tomb 95 that was built during the

reign of Amenhotep II. The artifact was discovered in debris inside the shaft.

It had with it the linen wrapped foot and leg, which show evidence that the amputation was cleaned, and prepared for the device. The amputation is completely healed which indicates that the owner lived

long after the accident using the prosthesis.

A prosthetic big toe discovered still on its mummified foot, is in the exhibit. It was among artifacts recovered from Tomb 95 that was built during the

reign of Amenhotep II. The artifact was discovered in debris inside the shaft.

It had with it the linen wrapped foot and leg, which show evidence that the amputation was cleaned, and prepared for the device. The amputation is completely healed which indicates that the owner lived

long after the accident using the prosthesis.

Many old kingdom tombs hold treasure from the new kingdom. The evidence suggests that they were reused as chapels, tombs, and living

quarters. While cleaning the tomb of Nyntr that dated to Dynasty II, a group of statues was discovered. One of these will be in the exhibit and was discovered by P.

Monroe in Saqqara. It is the double statue of the Memphite Priest Amun-Emibt and his wife. Discovered in 1986, and dated to the 19th dynasty, the statue

is of fine limestone and artfully recreates the fabulous clothing and headdresses of the couple. In Abydos, in the burials of the Kings of Dynasties 1 and 2, is the upper part of a

statue of King Seti I who was the second King of Dynasty 19. It was discovered by Petrie at the Osirin behind the temple of Seti I.

In Omel Rakhem, 28 km west of Marsi Matrouh, a statue of a military general Nb-re was discovered in 1994 by a Liverpool expedition in cooperation

with the Egyptian archaeologists at Marsi Matrouh. This statue comes from the time when Rameses II was building military

forts on the edge of the delta in an effort to protect the borders from attack by the Libyans. Nb-re was a

military leader of the site. Also found was a chapel that contained statues of the god Ptah, the god of the

artisans, and the goddess of war Sekhmet.

Underwater archaeology began in 1933 in Alexandria. In the exhibit is the statue of Isis found by Frank Gudio in cooperation

with Ibrahim Durwish. The statue was found in four pieces and restored by Nadia and her team along with several

other gold artifacts. The statue may be the most beautiful yet recovered.

Excavations in the Bahariya Oasis

Bahariya is one of the five oases in Egypt. One day my colleague called to tell me that I had better come out to the excavation

that he had started in Bahariya. When I looked into the first tomb and saw so many mummies, with gold covering their

upper bodies, I was thrilled. This site became known as the Valley of the Golden Mummies, and Bahariya has become

famous because of it. The media coverage at this site was greater than any other excavation.

There began to be a lot of tourist pressure to see the site, and I began to worry

about keeping the tombs safe from harm. I compromised my usual position of not moving mummies from their resting place,

and decided to move five of the mummies to a museum near by. Of these five two are children. One is a girl inside her exquisite sarcophagus, the gold mask is presented smiling.

The boy is covered in a face mask with garlands, the style of the time. The children stayed in the Bahariya museum until this exhibition.

The people at Bahariya had become rich because of their trade in wine. They traded from upper to lower Egypt and because of this were able to

cover their mummies with gold.

The

other exciting find at Bahariya was a temple built for Bes, and recovered was a statue. The domestic deity Bes was a popular figure who had an ugly face with

the ears and mane of a lion and a headdress of tall plumes. He is baring his teeth in an ugly grimace, and can be frightening, but he

is also rather comical. He was the god of joy, sexuality, dancing and music. Since Bahariya was a center for wine production, the people’s adoration of Bes is

understood.

In the capital of Bahariya, a town called El-Bawiti, a surprise waited under one of the modern houses. Two

Egyptian young people came to see me at the excavation of the mummies. They told me that they knew where there was a tomb under a house in the El-Bawiti. They said that if they told me where the tomb was, would I give them jobs

in the antiquities service? I followed them to a section of the capital and they led me into a house, and

through to the bathroom. In the bathroom floor was a hole. I climbed down into the hole, which was 10 meters deep, and couldn’t believe my

eyes. I had discovered the tomb of a governor of Bahariya in the 26th Dynasty, Djed-Khonsu-Euf-Omkh.

A large sarcophagus, weighing 16 tons was in the tomb, and from this tomb a maze of corridors and other rooms were discovered. The strangest thing that I had ever seen surrounded the sarcophagus.

A yellow powder, with a very bad smell, was poured all around the site

and was a half meter deep. It took my team two weeks to remove the powder, which turned out to be ground hematite.

This powder was used as a pigment for paint and such, but why the people chose to pour it around the tombs is still not understood. After that we decided to lift the lid of the sarcophagus.

It was so heavy it took five hours to move. I worked there with my old team, all the old musketeers, and it was the

best five hours in my life. We found inside the sarcophagus, another sarcophagus of alabaster. And inside that one was a third made of limestone.

When we moved the limestone sarcophagus to the north, we found under it the remains of a wooden sarcophagus. Here

were the remains of a deteriorated mummy with nine gold amulets. These will be in the exhibit.

North of the

governors tomb was the tom of his wife, Nasesa II. Her sarcophagus contained 103 pieces of gold. On one of the pieces the artist tried to write the name Wah-ib-re

representing one of the four sons of Horus. The third tomb in the maze was for the governors father Badi. Before this excavation was over we demolished twenty houses and it took us three months to clear the site. All of the tombs are located 10 meters under the surface and the water table under

the town made it a very dangerous excavation.

Conclusion

;We, the Supreme Council of Antiquities, would like to express our appreciation for the contribution made by foreign scholars like August Marriette, Gaston Maspero,

Heinrich Brugsch, Amelia Edwards, Flinders Petrie, and a host of others; they filled the museum with magical, awe inspiring artifacts that have captured the

hearts of people all over the world. We also recognize scholars like Rifaa El Tahtawi, Ali Mubarak, and especially Ahmed Basha Kamal whose passionate love of

their country broke down political barriers that had prevented Egyptians from fully appreciating their own history. We

want to recognize political leaders like Mohammed Ali, Khedive Said, Khedive Ismail, and Khedive Tawfiq whose efforts to modernize Egyptian archaeology,

helped to stem the loss of artifacts, and create conservation and educational programs.

We acknowledge the efforts of archaeologists, scholars, and politicians from around

the world, who believed that Egypt should control its own destiny. We are grateful to all those involved in the wonderful new renovations,

and the new collection, and together we proudly celebrate the One Hundredth

birthday of the Cairo Egyptian Museum.

History of the Museum Timeline

1797

There

is no Egyptian Museum. Most archaeology in Egypt is under French control.

Egyptians have little or no influence as to what becomes of ancient

artifacts, which are freely exported all over the world. Decorated sarcophagi are a favorite gift in England and France.

Egyptians are contributing to the country’s loss of its historical by digging for hidden treasures, and selling them to foreign collectors.

1835

Mohamed Ali, in an effort to stop the plundering of antiquities,

establishes the first Antiquities Service of Egypt. He creates a program to

exhibit and conserve the ancient artifacts. An Ottoman appointee, he was in favor of opening Egypt to the western

world. To increase tourism, and

establish the ownership of the ancient artifacts, he asks Yusuf Diya Effendi to

propose a sight for an Egyptian museum in Azbakia. Ali asked the Minister of Education to make a full report, documenting

the archaeological sites, and to assure that the artifacts are sent to the store

rooms in Azbakia. The death of Ali stalls the progress.

1848

In

order to protect the artifacts Khedive Abass I moves them to a hall in the

Citadel. Austrian Duke Maximillian visits the collection and is so impressed

that Khedive Said gives him the collection as a gesture of good will.

1855

Khedive Said orders the police to be more vigilant in watching for

Egyptian Antiquities being sold or exported. Auguste Marriette hurriedly excavates at Saqqara and discovers the

Serapeum of the Apis Bull. Most of

the artifacts discovered are secreted away to France.

1858

Khedive Said establishes the Egyptian Antiquities service and appoints

the first head, Auguste Marriette. Marriette begins a program to document

excavations, and attempts to take up the failed project of Ali to establish a

formal museum. Due to lack of French and Egyptian response, he renovates an old

mosque in Boulak to be used as a temporary museum, collecting from various

magazines around Egypt and Azbakia.

1859

Draag Abou-El Naga: The

intact tomb and treasures of Queen Iah-Hotep is discovered by Marriette her sarcophagus captures the heart of Khedive Said.

1863

Khedive Said finally orders that an Egyptian museum be built in Boulak. It opens during the reign of Khedive

Ismail.

1869

Ali Mubarak and Heinrich Brugsch establish the first school of Egyptology

in a rat and bat infested villa near the Boulak museum. It closes in 1874 due to Brugsch’s absence and Marriette’s hostility

(he is afraid for his position), which derails Egypt’s first attempt at

training its own Egyptologists.

1878

The Boulak museum, built on the Nile,

is flooded and severely damaged. Marriette begins to ask authorities for a

better and more permanent location for a museum.

1879

Rifaa Al-Tahtawi returns from being educated in Paris with a new

philosophy. Improve the national conscious

of Egyptians, and awaken their appreciation of their ancient monuments. He

succeeds in awakening several young scholars who believe in Egyptians being

included in their countries archaeology.

1881

The month that Marriette passes away, he extracts a cabinet resolution

that “hereafter no Egyptian monument shall be given to any power . . . not

forming a part of the Egyptian territory”. Gaston Maspero succeeds Marriette

as head of the Egyptian Antiquities

Service. Ahmad Kamal graduates in

France, and carries on the work of increasing awareness about Egyptian heritage.

Maspero shows his respect for Kamal by including him in the group which

publishes Catalogue de General. Kamal opens a tiny school of Egyptology at the Boulak museum. The

government funds for 5 students, but when they graduate uses the money to pay

their salary as antiquities inspectors. Due

to lack of funds the school closes in 1885.

1887

The Boulak Museum is so crowded; many artifacts are stacked against walls

or being stored in boats in Upper Egypt after they are excavated. Sarcophagi are stacked one upon the other.

The situation is desperate, and finally the Khedive donates one of his

palaces at Giza for a new museum.

1890

The new museum at Giza is opened, but it is still not large enough. Eventually Khedive Tawfiq decides to build a new museum in Cairo.

He announces an international competition for the best architectural

plans. Seventy three projects are

submitted. The winner is French

Architect Marcel Dowrgnon. The

Italians are awarded the museums construction, perhaps as consolation for

loosing the competition.

1897

Construction on the museum begins.

This

is the first museum in the world to be built as a museum instead of a

transformed palace or other building. Among

those present at a festival for the new museum are the reigning Prince Abass

Hilmi, and Gaston Maspero, who has returned as Director of the Antiquities Department.

1901

The museum key is given to Italian Architect, Alessandro Barasanti and he

begins, in March 1902, to move the objects from the palace in Giza, the old

museum in Boulak, and the Azbakia storage houses. Five thousand wooden carts are used to haul the treasures.

The first load contains about forty eight stone sarcophagi weighing about

1000 tons. It is difficult and

dangerous work. The officials notice that the statue of Kin Hor is missing and a

vigorous search begins. When discovered in a corner of the new museum, behind other

objects, rightened workmen admit that they had accidentally damaged the statue

and then hidden it in an effort to avoid punishment.

1902

The new building is completed and the artifacts are in place. Even though the design is Neo-classical, and the exterior reflects not

one Egyptian contribution, inside the

Pharonic influence persists. The

halls are similar to Pylons at the ancient temples, and the rooms inside the new museum are amazingly like resemble the rooms

in the temple at Edfu. In the

basement rooms, Ahmad Basha Kamal, the first Egyptian Egyptologist, works with

quiet dignity, to break down the barriers

that keep Egyptians out of archaeology. He

and Ahmad Lufti Al-Sayyid strive to prepare Egyptians to manage their own

archaeology. On July 13th the tomb of Marriette is moved to the new museum garden.

His will had indicated that he wanted is body to lie near the

ancient artifacts, that he had struggled

all his life to collect, protect, and properly exhibit. Maspero becomes the initial curator.

1910

Ahmad Kamal persuades the Ministry of Education to form an Egyptology

section in the Higher Teachers College of Cairo. At the Egyptian University he teaches his third class on ancient Egypt.

In recent years he published articles and books in Arabic and French about

Egyptian archaeology, Arabic grammar, and history.

1922

England declares Egypt an independent country which permits the Egyptian

government to keep all newly discovered artifacts. The contents of the tomb of a young king named Tutankhamen are uncovered

in the Valley of the Kings for the first time Egypt retains the artifacts of a site. Egypt takes control of all exportation, museums, antiquities, schools,

and the training of new Egyptian Egyptologists. Archaeology and politics become

forever linked in Egypt.

1951

Ahmad Kamal is recognized as the first Egyptian archaeologist.

His

great achievements in Egyptology, are honored by the placement of a bust, made

in his likeness, in the garden of the Egyptian museum.

2002

Centennial celebration of the Egyptian Museum. Museum renovations

complete with a new exhibition area in the basement, new exterior lighting, and

a huge new parking structure are unveiled. Zahi Hawass, and the Supreme Council of Antiquities bring artifacts from

all over Egypt to be viewed by the public for the first time. A catalogue featuring

100 of the finest newly

exhibited artifacts, photographed by Ken Garrett, are published as a memoir of the centennial celebration.

At last the hopes and dreams

of generations of Egyptian and

foreign scholars is being recognized, the museum school of Egyptology, which

struggled and failed so many times in the past is scheduled to open in January,

2003. The children of Cairo are not

left out. A school that will teach

young Egyptians about their heritage, and the value of their antiquities, is

opened at the museum.

BACK

to The Plateau Homepage

The Cairo Museum is a portal through which the visitor is transported back to the mysterious realm of Ancient Egypt. It holds the treasures of the greatest civilization in the world.

This year is the centennial of the creation of the first permanent Egyptian Museum.

On December 9th, 2002 at a centennial celebration over two hundred and fifty hidden treasures of Ancient Egypt will be unveiled. I would like to recount how this new exhibit came about.

The Cairo Museum is a portal through which the visitor is transported back to the mysterious realm of Ancient Egypt. It holds the treasures of the greatest civilization in the world.

This year is the centennial of the creation of the first permanent Egyptian Museum.

On December 9th, 2002 at a centennial celebration over two hundred and fifty hidden treasures of Ancient Egypt will be unveiled. I would like to recount how this new exhibit came about. .jpg) One of the most exciting adventures was to bring the sarcophagus of Horwdja, dated to Dynasty 26, from Quesna, about 57 km. north of Cairo. It had been discovered in October 1992.

Horwdja, with his father and brothers held the title of priests of the Djed-pillar at the house of the God. One of the most important scenes found on the sarcophagus was the scene

of the family of the priest Hor-Djed. They are standing in front of the sacred tree with Isis and her sister Nepthys.

Another beautiful scene is that of Anubis sitting on a mummification tent. On the sarcophagus are twenty seven lines of hieroglyphics from the book

of the dead, representing about eighty nine chapters. Made of black granite, and weighing approximately 20 tons, it is 241 cm.

long, 100 cm. wide, and 145.5 cm high; moving it was going to be an enormous task.

One of the most exciting adventures was to bring the sarcophagus of Horwdja, dated to Dynasty 26, from Quesna, about 57 km. north of Cairo. It had been discovered in October 1992.

Horwdja, with his father and brothers held the title of priests of the Djed-pillar at the house of the God. One of the most important scenes found on the sarcophagus was the scene

of the family of the priest Hor-Djed. They are standing in front of the sacred tree with Isis and her sister Nepthys.

Another beautiful scene is that of Anubis sitting on a mummification tent. On the sarcophagus are twenty seven lines of hieroglyphics from the book

of the dead, representing about eighty nine chapters. Made of black granite, and weighing approximately 20 tons, it is 241 cm.

long, 100 cm. wide, and 145.5 cm high; moving it was going to be an enormous task. In 1990 excavations began at what was to become the cemetery of the pyramid

builders. The accidental fall of a horses hoof through a hole, uncovered the first tomb. The cemetery is located on a hill south of the pyramids of Giza.

The first tomb was a family tomb prepared with three false doors, the first for a man named Ptah-Shepsesu, and the others for his wife and son. The tomb also contains a small open courtyard.

The walls incorporate what appear to be left over stones that were used in the construction of the pyramid, temples, and official tombs. Nearly six

hundred small tombs of a variety of styles, and seventy more elaborate tombs were found at this site. Up to 6

ft. high many tombs have pyramidal shapes, some like beehives, and some like gabled roofs. Others have miniature

ramps and causeways, and some are miniature mastabas. In shafts under the tombs, simple rectangular burials contain skeletons

of the owners, whose budgets did not include mummification.

In 1990 excavations began at what was to become the cemetery of the pyramid

builders. The accidental fall of a horses hoof through a hole, uncovered the first tomb. The cemetery is located on a hill south of the pyramids of Giza.

The first tomb was a family tomb prepared with three false doors, the first for a man named Ptah-Shepsesu, and the others for his wife and son. The tomb also contains a small open courtyard.

The walls incorporate what appear to be left over stones that were used in the construction of the pyramid, temples, and official tombs. Nearly six

hundred small tombs of a variety of styles, and seventy more elaborate tombs were found at this site. Up to 6

ft. high many tombs have pyramidal shapes, some like beehives, and some like gabled roofs. Others have miniature

ramps and causeways, and some are miniature mastabas. In shafts under the tombs, simple rectangular burials contain skeletons

of the owners, whose budgets did not include mummification.

From this upper cemetery, and part of this exhibition, are the statues of Inty-Sdu found in the Serdab of his tomb. Cut into

bedrock, and intact, Inty-Sdu’s tomb had a simple niche in the wall covered with mudbrick. We noticed this

because there was a small hole in the wall. I peered inside the niche with a flash light and staring at me were the eyes of a statue.A far greater surprise awaited me after I removed the mudbrick covering

the niche.Four statues stared back at me. The middle statue is the largest and is flanked on the right with two

smaller statues, and on the left is another small statue. We discovered the remains of a fifth wooden statue which had stood at the

far left.Disastrously, when we opened the tomb, the flow of oxygen had instantly disintegrated it. This wooden statue must have been added after the others were finished in

order to fulfill the ancient Egyptian appreciation of symmetry.

From this upper cemetery, and part of this exhibition, are the statues of Inty-Sdu found in the Serdab of his tomb. Cut into

bedrock, and intact, Inty-Sdu’s tomb had a simple niche in the wall covered with mudbrick. We noticed this

because there was a small hole in the wall. I peered inside the niche with a flash light and staring at me were the eyes of a statue.A far greater surprise awaited me after I removed the mudbrick covering

the niche.Four statues stared back at me. The middle statue is the largest and is flanked on the right with two

smaller statues, and on the left is another small statue. We discovered the remains of a fifth wooden statue which had stood at the

far left.Disastrously, when we opened the tomb, the flow of oxygen had instantly disintegrated it. This wooden statue must have been added after the others were finished in

order to fulfill the ancient Egyptian appreciation of symmetry.

.jpg) The New Kingdom, Dynasties 18 to 20 is considered the golden age of Egypt. From the Valley of the Kings

is the tomb of King Tut. Many of the 6000 artifacts have never been seen by the public, and so they will be

included in the hidden treasure exhibit. Recently restored gilded and inscribed leaves that cased furniture, two painted wooden boxes, beautiful and

extravagantly painted wooden boats, a golden pectoral, and a winged scarab holding the sun disk are among the newly restored artifacts. When the conservation team was working on a jewelry box, from the

collection, they were surprised to find a piece of jewelry that had never been catalogued.

The New Kingdom, Dynasties 18 to 20 is considered the golden age of Egypt. From the Valley of the Kings

is the tomb of King Tut. Many of the 6000 artifacts have never been seen by the public, and so they will be

included in the hidden treasure exhibit. Recently restored gilded and inscribed leaves that cased furniture, two painted wooden boxes, beautiful and

extravagantly painted wooden boats, a golden pectoral, and a winged scarab holding the sun disk are among the newly restored artifacts. When the conservation team was working on a jewelry box, from the

collection, they were surprised to find a piece of jewelry that had never been catalogued.

.jpg) A prosthetic big toe discovered still on its mummified foot, is in the exhibit. It was among artifacts recovered from Tomb 95 that was built during the

reign of Amenhotep II. The artifact was discovered in debris inside the shaft.

It had with it the linen wrapped foot and leg, which show evidence that the amputation was cleaned, and prepared for the device. The amputation is completely healed which indicates that the owner lived

long after the accident using the prosthesis.

A prosthetic big toe discovered still on its mummified foot, is in the exhibit. It was among artifacts recovered from Tomb 95 that was built during the

reign of Amenhotep II. The artifact was discovered in debris inside the shaft.

It had with it the linen wrapped foot and leg, which show evidence that the amputation was cleaned, and prepared for the device. The amputation is completely healed which indicates that the owner lived

long after the accident using the prosthesis.