|

Secrets of

the Valley of the Kings

Zahi Hawass

It is the dream of every archaeologist to dig in the Valley of the Kings,

the burial ground of the monarchs of the New Kingdom (ca. 1500-1100 BC).

Of all the sites in Egypt, this is one of the most magical. It is hard to

believe that, of the 63 tombs found in the valley, not one was officially

discovered by an Egyptian archaeologist.

For the last two centuries, the valley has been explored by adventurers

and tomb robbers as well as archaeologists. The most exciting discovery

here, indeed the most fabulous find in the history of Egyptology, was made

on November 4, 1922, when British excavator Howard Carter found the intact

tomb of Tutankhamun (known as KV 62). The story of this great find, and

the magnificent objects that were recovered (over 5,000 of them) still

captures the hearts of the world, and overshadows many of the other

important discoveries that have been made in the Valley, such as the

mostly-intact tomb of Yuya and Tjuya, who were probably the

great-grandparents of King Tut, and the tomb of Amenhotep II.

When I was young, I went to work on the West Bank at Thebes, where the

Valley of the Kings is located, with the University of Pennsylvania-Yale

Expedition to Malkata. Malkata is the site of the palace of Amenhotep III,

the grandfather of Tut. It lies in the floodplain south and east of the

royal Valley. I was one of over 30 young Egyptian archaeologists working

with foreign expeditions in the area. This was during the 1973 war, and we

were not allowing foreign archaeologists to work at any other sites, so

many of us were was gathered at Thebes.

My colleagues and I used to meet in the afternoon at El Marsam Hotel,

owned by a man named Shiekh Ali Abdel Rassoul, the last surviving member

of the Abdel Rassoul family. In the 19th and early 20th century, the Abdel

Rassouls were known as the most successful tomb robbers in the area. In

1871 (or perhaps before), they had stumbled across a deep shaft that led

to a series of corridors containing the mummies of many of the kings and

queens of the New Kingdom. The royal mummies had been hidden in this

secret cache during the Third Intermediate Period, when the central

government could no longer guard the Valley of the Kings. The family kept

the find hidden for ten years, until the Antiquities Service tracked them

down and forced them to reveal their secret. The Abdel Rassouls had also

led Victor Loret, then head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, to the

Bab el-Gasus, a tomb containing over 150 mummies and coffins from the

Third Intermediate Period, and to the tomb of Amenhotep II in the Valley

of the Kings, where more royal mummies had been cached in ancient times.

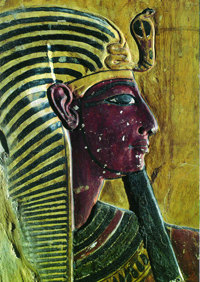

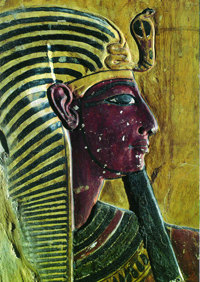

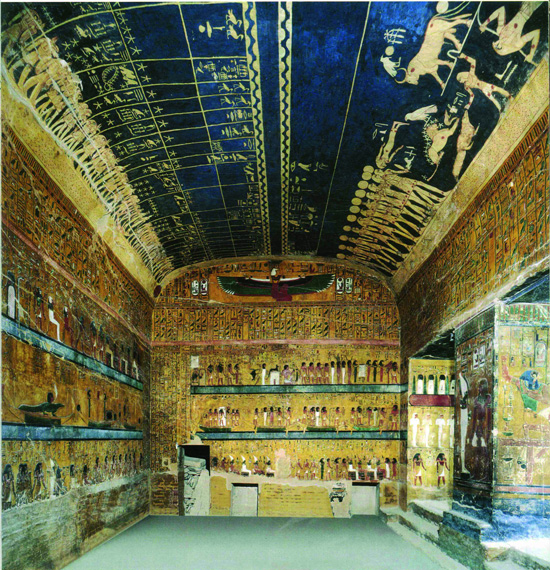

The Tunnel in the Tomb of Seti I

My friends and I used

to sit with Sheikh Ali at night, laughing and playing games. But the

Sheikh felt that I was different from the others, and he would

single me out. We spent a lot of time talking, just the two of us,

about many different things. One day he asked me to go with him to

the Valley of the Kings, into the burial chamber of the tomb of Seti

I. |

He pointed out the entrance

to a roughly-cut tunnel, which he told me descended for about 100 meters

(300 feet) and ended in the secret burial chamber of Seti I.

I found out later that

although there certainly is a long tunnel, Seti I’s real burial cannot be

hidden at the end, as he was clearly buried in the main part of the tomb.

The king’s massive alabaster sarcophagus was found in the burial chamber

tomb by Italian adventurer Giovanni Belzoni in 1817.

He took this to England, and

it is now displayed in the Sir John Soane Museum in London. More important

is the fact the Seti I’s mummy was found in the first royal mummy cache,

the one found by the Abdel Rassouls in 1871. But Sheikh Ali told me that

one day I would become an important archaeologist, and it would be my

destiny to explore this mysterious tunnel.

None of the other tombs in the Valley of the Kings has such a tunnel, and

Egyptologists have not been able to explain exactly what it is or why it

is there. Some have suggested that it is symbolic, and leads down into the

underworld, where the king’s soul would join with the ruler of the dead

Osiris so that he could be resurrected. But why is he the only king to

have this? How do we know that this is really what it means?

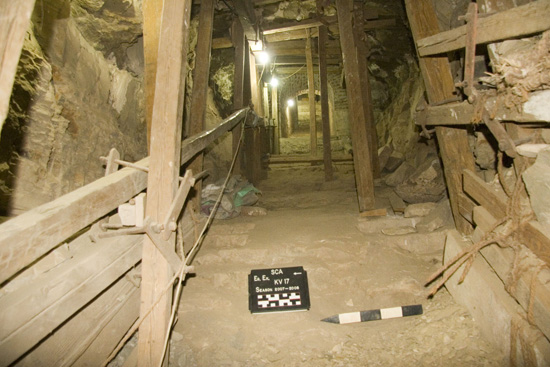

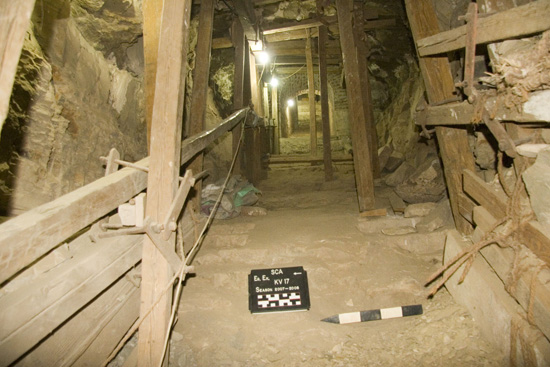

When I became

the head of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, I decided that I wanted to

explore this tunnel. In 2003, I entered the tunnel for the first time. I

attached myself to a thick rope for safety, and a light was set up so that

I could see.

I wore my famous hat, and

took a measuring tape with me. I descended along a gentle slope, but at

the 252-foot mark, I decided it was too dangerous to continue. Rock was

falling, and the tunnel was clearly unstable. It was also becoming

narrower, and I knew that we would have to do serious work to make the

tunnel safe before we could explore further.

I entered for a second time

as part of a program made by David Jackson of KCBS in Los Angeles about

Tutankhamun and the Valley of the Kings.

Just this year, I decided to

make Sheikh Ali’s dream come true. As part of the first truly Egyptian

archaeological project in the Valley of the Kings, we are now doing a

scientific study of the tunnel. A geological survey has been carried out,

and we have begun clearance, working slowly to guarantee the safety of my

all-Egyptian team. This team, which works under my supervision, is headed

by Dr. Tarek El Awady. To date, we have cleared about 40 meters (120 feet)

of the tunnel. The results are intriguing: among the finds are a number of

non-royal New Kingdom shabtis, dating to near the reign of Seti I. I hope

that by the end of 2008 we will be able to reveal the final mysteries of

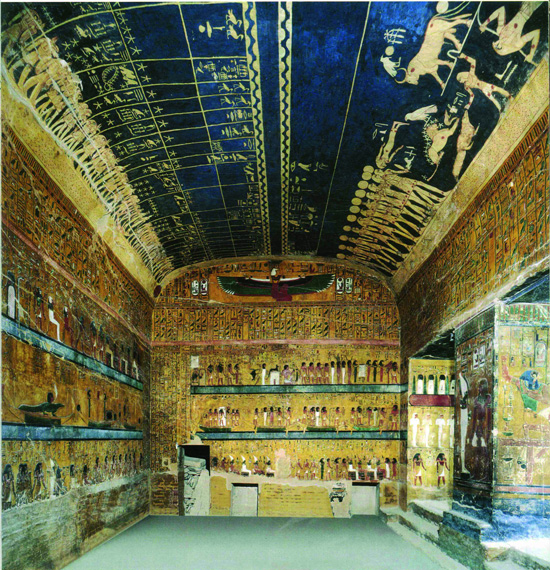

the tomb of Seti I, the most beautiful tomb in the valley.

The Tomb

of Ramesses VIII?

In 1974, during my second season in Thebes, I spent a magical night in the

Valley of the Kings. It was during the summer, and there was a full moon.

I asked Sheikh Nagdy, the

chief of the guards on the West Bank, to accompany me to climb the Qurn,

the pyramidal peak that stands sentinel over the Valley. Sheikh Nagdy was

the son of Sheikh Abdel Maugoud, who had known Howard Carter personally.

Sheikh Maugoud told me once that he had seen Evelyn Herbert, the daughter

of Lord Carnarvon, enter the tomb of Tutankhamun at night several times.

He believed that Howard Carter was in love with her, not, as many people

think, that she was in love with him but he was indifferent. When I

climbed the Qurn that night, I felt magic in the silence that surrounded

me.

Later, I became interested in pyramids and spent most of my life

excavating around them. But my eyes would always turn again to the Valley

of the Kings. A few years ago, there was an English expedition working in

the Valley, looking for the lost tomb of Nefertiti. They used radar to see

what might be hidden below the ground, and found an “anomaly” that they

tentatively identified as KV 64, an unknown tomb. This anomaly is very

interesting, and the area should be explored some day, but right now we

are working in a different area of the Valley. We are hoping to find the

tomb of Ramesses VIII, which has never been discovered, somewhere between

the tomb of Merenptah (KV 8), son and successor of Ramesses II, and the

tomb of Ramesses II himself (KV 7).

The team that I have

appointed to search for the tomb of Ramesses VIII is headed by Afifi

Rohiem, who has worked with me for many years at Giza. We began our work

to the north, south, and west of the tomb of Merenptah. We have

rediscovered ancient graffiti recorded by the great scholar Jaroslav

Czerny. One of these was written by the 18th Dynasty vizier Userhat, who

says that he built a tomb for his father, Amennakht, in this area. The

site is littered with large blocks, which we are moving in our search for

lost tombs – and we are finding tantalizing clues that something is hidden

here. In the area to the south of Merenptah’s tomb, we found a cutting in

the bedrock, but the rubble at the entrance to whatever lies beyond has

been disturbed. If there is a tomb here, it is unlikely to be intact.

However, another cutting, to the north, appears to be undisturbed. We have

also found workmen’s huts, which we have recorded carefully. We are

planning to bring in very sophisticated radar that can see 20 meters down,

and hope that this will help guide us in our work.

There are many secrets still hidden in Valley of the Kings, and on the

West Bank of Luxor. The real tomb of Amenhotep I is still being debated.

Some scholars believe that he was buried in KV 39 (in the Valley of the

Kings), and others believe that his tomb is at Dra Abu el-Naga, at the

northern end of the Theban necropolis. Now a Polish archaeologist is

exploring his theory that the tomb is hidden in the rocky cliffs behind

the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari, and, although the king’s mummy

and coffin were found in the first royal mummy cache, he dreams that it is

still intact. The tomb of Thutmose II is also still not definitely

identified. Was he buried in KV 42, or DB 358, or is his tomb still

unknown? (Again, it is unlikely to be intact, since his body was in the

first royal mummy cache.) Where is the Amarna royal family: Akhenaten

(whose body may be the one that was found in KV55), the elusive Smekhkare,

Nefertiti, and their princesses? There are many other queens of the New

Kingdom whose burials have not yet been found; any of these, if found

intact, are sure to be absolutely spectacular; if robbed, they would still

be fantastic. As I always say, you never know what secrets are hidden

beneath the sand of Egypt.

BACK

to The Plateau Homepage |