Considered to represent the pinnacle of the Pyramid Age, the Great

Pyramid is the epitome of the knowledge and experience of all previous pyramids.

Khufu had every advantage in growing up in an atmosphere of the several pyramid

building projects of his father Sneferu. In light of this it becomes easier to

understand that Khufu was more than qualified to oversee and organize the grand

task of building the monument that is the only surviving member of the Seven

Wonders of the World. So much uninformed speculation abounds as to the origin,

engineering and construction of the Great Pyramid, though we have a wealth of

archaeological evidence to piece together much of the accomplishment. Recently,

remnants of ramps have been found by Dr. Zahi Hawass on the south side of the

pyramid that attest that some type of ramping was indeed used in the

construction of this monument. The attribution of the pyramid to King Khufu is

supported by workman’s markings that were found in the pyramid in small

chambers that were never intended to be opened. The precision with which the

pyramid was executed is often the source of marvel and speculation. It is likely

that the attention to this precision was related to the many structural problems

encountered in previous pyramids. To minimize many of the previous errors, the

attention to precision produced a pyramid whose base is level within 2.1 cm

(less than 1 inch!), with the only difference in the length of the sides being

4.4 cm (1.75 in). The base covers an area of 13 ½ acres. The blocks used in the

pyramid are large, with a commonly stated average of 2.5 tons. Many blocks are

indeed smaller than this, the blocks toward the top decrease in size. Some of

the casing stones at the base are very large, weighing as much as 15 tons. The

heaviest blocks are the granite blocks used to roof the kings chambers and the

weight relieving chambers above the king’s chamber. These are estimated to

weigh from 50 to 80 tons each!!

|

|||||||||||

|

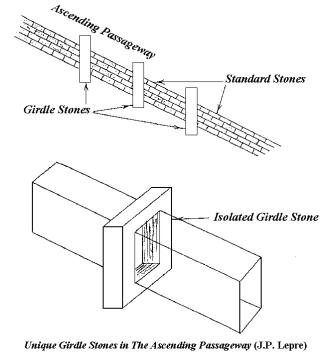

At a distance of approximately 60 ft from the entrance there is a hole through the masonry roof of the descending passageway which leads to the first ascending passageway seen in a major pyramid. This passage is 129 feet in length and rises at a gradient of 26°2’30”. Its lower end was plugged with three 7-ton granite slabs, which are still in place. Currently, one enters the ascending passageway through a hole that was hewn around these slabs from an intrusive entrance. The ascending passageway leads to the Grand Gallery. One unique and ingenious feature of this passage is that it is supported by a series of four single stones which were hollowed out. Through these the corridor was laid, these have become known as the “girdle stones”. There are also 3 “half girdles” which are actually two stones combined for the same purpose. At the point where the Grand gallery is first entered there is a level landing which leads straight to the middle chamber.

|

|

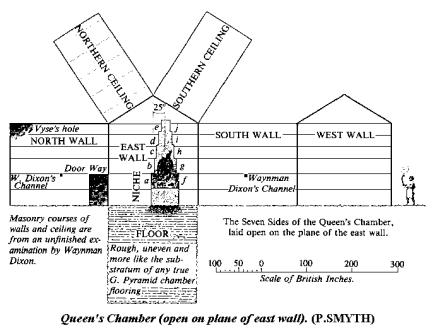

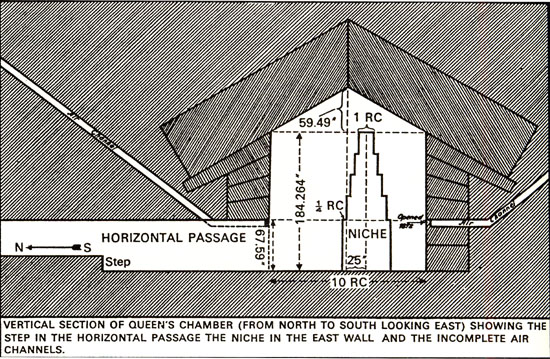

the evidence proposed to support this

theory include the fact that the floor appears to be only roughly finished.

Also, there are small rectangular apertures, in the north and south walls which

lead to small shafts which appear to have been prematurely discontinued. Similar

shafts in the upper chamber pierce through the surface of the pyramid. The

southern shaft of this chamber has

been determined by robotic exploration to abruptly end with a plugging block.

The northern shaft has yet to be explored, but no exit aperture has been found

outside the pyramid.

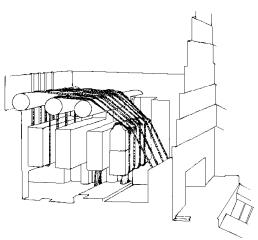

At the south end of the Grand Gallery there is an entrance that leads to an antechamber between the grand gallery and the main chamber. It has a configuration that housed large portcullis blocking slabs which were designed to be lowered to seal the chamber after the burial of the king.

The

Main Chamber

The main chamber, known as the King’s

Chamber, is a remarkable chamber built entirely of rose granite. It is situated

at the 50th course of masonry. The stones used to construct this

chamber are the heaviest known stones in the entire pyramid. There are 21 stones

comprising the floor alone. The walls are comprised of 101 stones and there are

9 huge beams forming the ceiling. This chamber contains the granite sarcophagus

and also has small apertures leading to shafts on the north and south walls.

Unlike similar shafts in the Queen’s Chamber, these pierce through the outer

surface of the pyramids. Presently there is a ventilation fan fitted into the

southern shaft and this regulates the moisture in the chamber, minimizing the

damage caused by the moisture produced by the breath and sweat of visitors. As

with all other exposed surfaces in this pyramid, there are no inscriptions or

carved reliefs on the chamber walls.

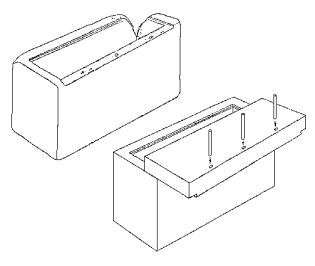

The

coffer is no longer has it’s lid and the southeast upper corner has been

broken away. It is also made from a single block of rose granite weighing about

3.75 tons. Its western edge sports three drilled pinion holes that were used to

hold the lid in place after the interment. The lid would have weighed over 2

tons and was slid into place within angled grooves. The size of the coffer

necessitates that the chamber was built with the coffin already in place – it

would not have fit through the entrance, nor would it have fit through the lower

section of the ascending passageway.

The

Relieving Chambers

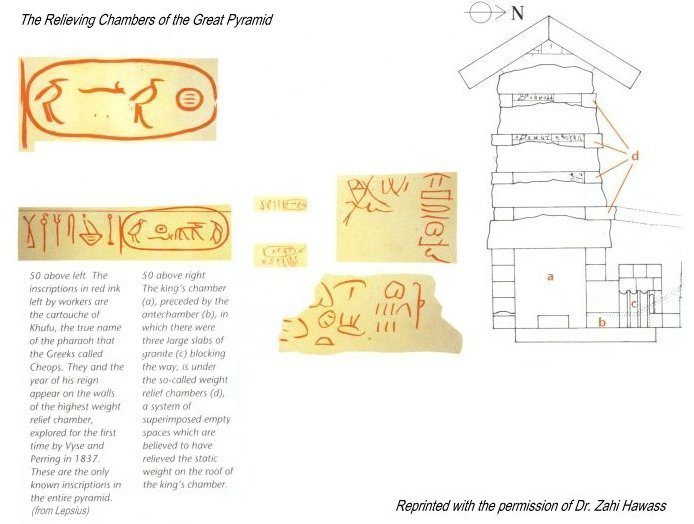

When blocks were cut at the various quarries

they were organized and cataloged in order to prepare them for transportation to

the site and final placement during assembly. The blocks were marked in red ink

to fulfill this purpose and these markings would include the placements

information and often also the name of the work-gang that would be directly

working with the blocks. When the blocks were placed the markings were rubbed

off of any surface that would be showing. Fortunately, they often did NOT remove

these markings on surfaces which were not intended to be exposed. This has left

us with some examples of these markings which can be seen on many sites. We will

see many examples of these types of markings.

In the Great Pyramid, chambers were discovered

by blasting with dynamite that are located above the main burial chamber. These

are commonly referred to as “relieving chambers” as they appear to have been

included to relieve the weight of the blocks above the main chamber to preserve

that chamber from collapse. Evidence that these chambers were never meant to be

entered can be seen by the presence of workman’s markings in red ink. As an

added bonus, the markings in these small chambers provide us with both the name of the work-gang responsible

for those blocks, but also with the name of the king that built the pyramid,

King Khufu. This is the most compelling evidence of the ownership of the pyramid

that we see in any pyramid until the Pyramid of Unas in the 5th

Dynasty.

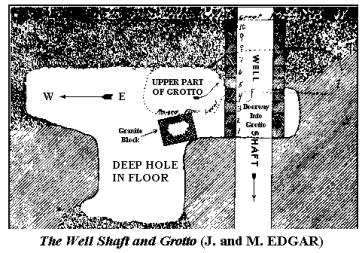

Another

unusual feature if the Great Pyramid is the Well Shaft and grotto.

Another

unusual feature if the Great Pyramid is the Well Shaft and grotto.

This

well shaft is a roughly cut passage that connects the lower portion of the Grand

Gallery with the lower portion of the descending passageway. It is about 28“

square throughout its course and in places there are rough footholes. It is

believed that this obscure passageway was cut to act as an escape route for the

workers that would slide the large portcullis blocks into place sealing the

burial. Portcullis blocks were lowered into place in the antechamber sealing off

the main burial chamber and then three other 7-ton granite plug stones were slid

into the ascending passageway sealing off the entire array of upper chambers.

The workers responsible for the plugging would be trapped in the Grand Gallery

and so it is theorized that the well shaft was cut to allow for their escape. In

hearing of this passage one may think that it defeats the entire purpose of the

plugging blocks, but this passage is tortuous and extremely dangerous to climb

through. The Grotto is a small cavity located where the pyramid masonry meets

the core, though this is 25 feet

higher than the pyramids base as this is an area in the bedrock where there was

an outcropping rise in the central pyramid plateau that was used to full

advantage in the pyramid core, alleviating the need for filling material in this

section. It is thought that the Grotto may have originally been a small natural

cavity in the bedrock that was enlarged during the tunneling of the well shaft.

Mysteriously, there is a large granite block in the grotto, and it is unclear as

to how this stone got here or why it was left here. The most likely explanation,

as evidenced by its mere dimensions, is that this granite block is one of the

portcullis stones that originally blocked the antechamber.

After the escape of the

workers, the opening at the bottom of the well shaft was probably sealed with a

block of limestone that was designed to completely camouflage the passageway.

The

Khufu Pyramid Complex

The

Mortuary Temple

|

|

All that remains of the Mortuary temple of

Khufu are the remnants of the floor which was paved with black basalt. The floor

plan is much larger than the chapels associated with the Pyramid at Meidum and

the Bent Pyramid. The temple is very different from Mortuary temples that

preceded it or followed it. Sockets are evident in the floor which would have

held the granite pillars that comprised the colonnade that surrounded an open

court. At the western end of the temple is a recess thought to be a sanctuary

and signs of an outer wall. This is flanked by two vestibules. The interior

walls were made of limestone and were carved with fine reliefs. There are no

sign that there were any niches in this temple. This temple is the first known

temple to make use of limestone, granite and basalt.

The Valley Temple of Khufu

The

Valley Temple of Khufu has not yet been found though it is assumed that it

existed and lies at the end of the causeway. Presently, this leads to under the

present day village of Nazlet el-Saman, and has yet to be uncovered and

explored.

The Boat Pits

Five

boats pits have been discovered in the immediate area around Khufu’s pyramid.

Two are on the southern side of the main pyramid, two are on its eastern side

flanking the Mortuary temple and the last is to the north of the causeway. In

the southeastern pit the first intact boat was found dismantled in the pit. This

was reassembled and now resides in a special climate controlled museum on the

south side of the main pyramid. The southwestern pit has been found to contain

yet another boat which still remains in situ.

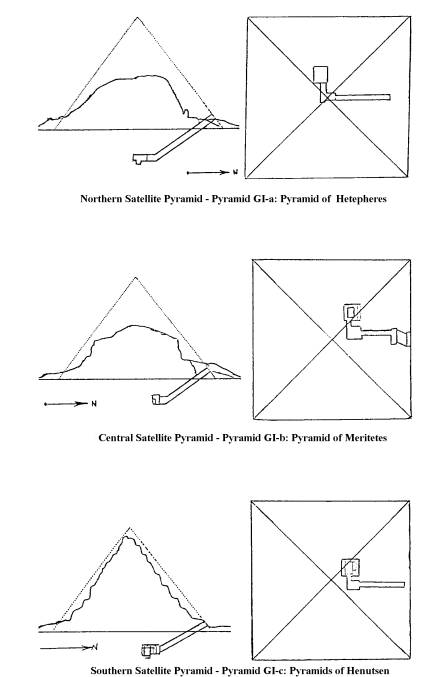

The Satellite Pyramids of Khufu

|

The Great

Pyramid has three smaller so-called satellite pyramids on its north

side. These are often referred to as the Queen’s Pyramids, referring

to three queens that were associated with these pyramids. The

northern-most pyramid is known as the Pyramid of Hetepheres

(known to Egyptologists as GI-a), the next the Pyramid of Meritetes

(GI-b), and the southern is known as the Pyramid of Henutsen (GI-c) Each of these smaller pyramids consist

of a sloping descending

passageway that leads from the opening to a main chamber after taking a

short right angle turn. These chambers are subterranean and their

interiors are carved into the bedrock of the plateau. The exteriors are

badly damaged with pyramid GI-c being the most intact. There is evidence

that all three pyramids had an adjoining chapel, similar to the Mortuary

temple on the larger pyramids. The northernmost pyramid (GI-a) was probably originally intended to be built slightly east of its present location. This is evidenced by the leveling of the rock at that original location and the beginnings of a substructure. This apparently would have interfered with a shaft cut for the reburial of Queen Heterpheres and so the pyramid was moved slightly west. Within the last few years, Dr. Zahi Hawass has discovered the probable satellite pyramid of Khufu north of the GI-c and south of the GI-b pyramid between these and the great pyramid. The only remains of this include a T-shaped trench, including small descending passage and chamber. The sides of the chamber are inwardly inclined which is similar to those of the galleries under the east side of the Djoser Step Pyramid. The possible pyramidion for this pyramid was also found in fragments and now stands reassembled at the site. |

This

is an excerpt from the book,

Guardian's Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Primer,

available soon.

Copyright

© 2000-2005 Andrew Bayuk

All Rights Reserved

Credits for Illustrations

The Great Pyramid – diagrams - Guide to the Pyramids of

Egypt, Alberto Siliotti

Copyright

© 1997 All Rights Reserved

The Grand Gallery in the Great Pyramid - The

Pyramids of Egypt – I. E. S. Edwards

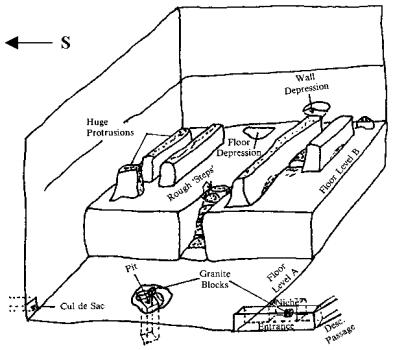

Illustration of the Subterranean Chamber of the Great Pyramid - The

Egyptian Pyramids -

J.P. Lepre

Illustration of the girdle stones in the Ascending Passageway of the Great

Pyramid - The

Egyptian Pyramids -

J.P. Lepre

The Antechamber of the Great Pyramid showing Portcullis blocks - The

Complete Pyramids – Mark

Lehner

Copyright

© 1997 All Rights Reserved

Illustration of the rose granite coffer of Khufu - The Egyptian Pyramids – J.P. Lepre

The Relieving Chambers – J & M Edgar

Plan of the Well Shaft and Grotto of the Great Pyramid – J & M Edgar

Bibliography and Suggested Reading

Edwards,

I.E.S. The

Pyramids of Egypt.

New York and London, Penguin Books, 1985

Fakhry, A. The

Pyramids. Chicago and London, 1969

Hawass,

Zahi, The

Pyramids of Ancient Egypt. Pittsburgh. 1990

Lehner, Mark. The

Complete Pyramids.

London. 1997

Lepre, J.P.

The

Egyptian Pyramids.

North Carolina. 1990

Mendelssohn, K. Riddle

of the Pyramids. New York. 1974

Petrie, W. M. F. The

Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh. London. 1883

Siliotti, Alberto. Guide

to the Pyramids of Egypt, Cairo, 1997

Andreu, Guillemette, Egyptian

Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Ithaca and London. 1997

Weeks, John. The

Pyramids. Cambridge, 1971

Back to Guardian's Great Pyramid Homepage

Return to Guardian's Ancient Egypt Bulletin Board

The

pyramid has three main chambers. The original entrance of the pyramid is located

7.29 m (24 ft) east of the center of the pyramid on the north face, at a height

of 16.76 m (55 ft) above ground level.

The

pyramid has three main chambers. The original entrance of the pyramid is located

7.29 m (24 ft) east of the center of the pyramid on the north face, at a height

of 16.76 m (55 ft) above ground level.